Stars of Yesterday: Looking Back at the Best Fountain of Youth Stakes Winners

Improvements in advanced imaging and increased use of this medical technology at the track is proving critical in identifying potential injury hotspots in racehorses, prompting treatment before smaller issues turn into catastrophic problems.

In the sport’s multi-faceted approach to improving equine safety, such technology has been an important tool in reducing such incidents in the 15 years they have been tracked by The Jockey Club Equine Injury Database.

In the past decade, and increasingly so in the past five years, advanced imaging is playing a leading role in enhancing racehorse safety. Imaging encompasses several modes of scanning that have improved veterinarians’ ability to discover bone issues earlier and more comprehensively than they were able to do previously through radiography (X-rays) and ultrasound.

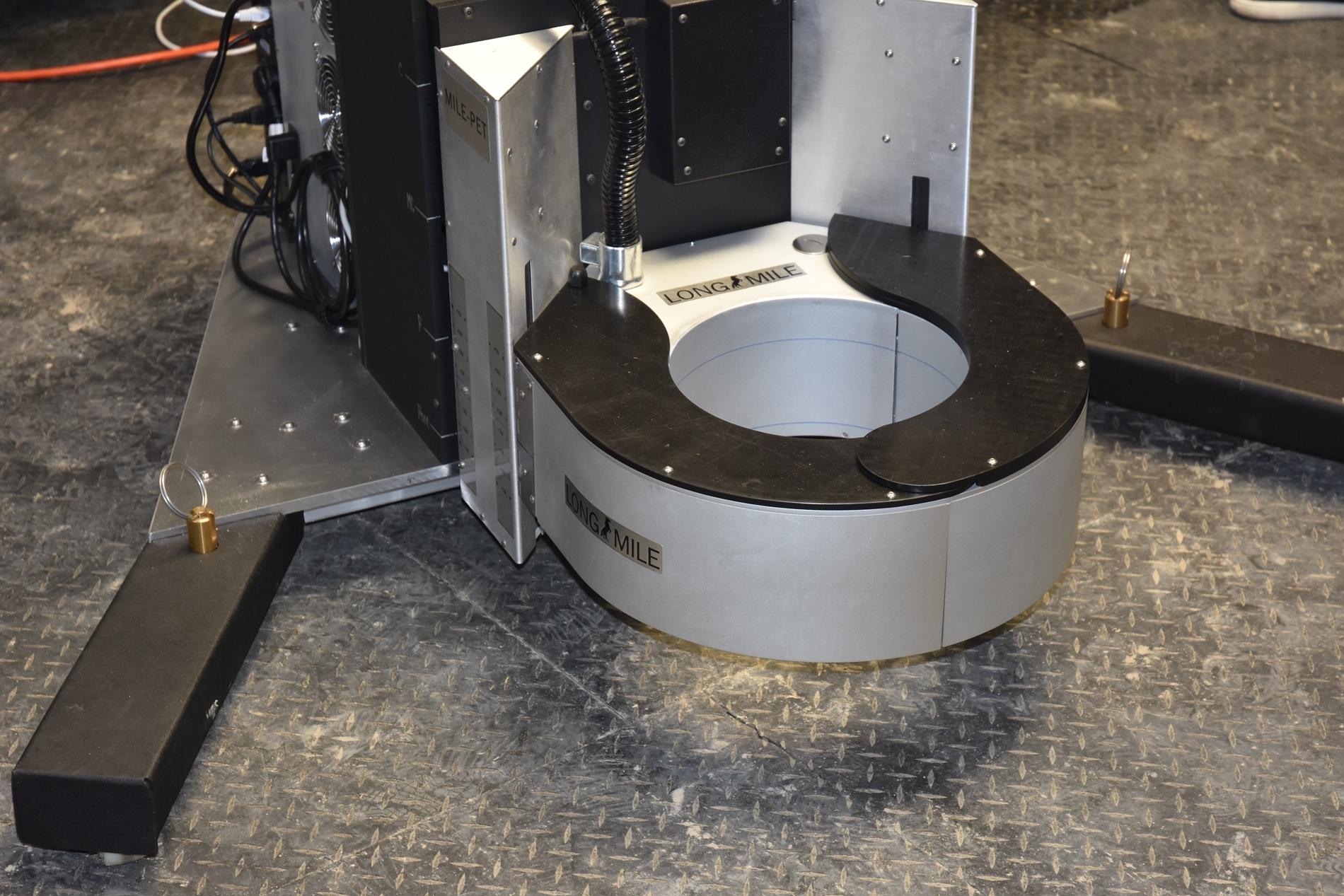

What started as a research project at the University of California-Davis less than a decade ago has yielded scanning modalities such as PET (positron emission tomography) scans, CT or CAT (computerized tomography) scans, MRIs (magnetic resonance imaging), and nuclear scintigraphy for use on horses that have been identified as harboring potential problems that keep them from safely training and racing.

Dr. Stuart Brown, vice president of equine safety at Keeneland, said a three-tier approach to equine safety was embraced coming out of last year’s American Association of Equine Practitioners conference. The first level consists of surveilling and selecting horses of interest because of bone issues or the potential for those issues. The second level is identifying the limb from which the lameness is emanating, and the third involves use of advanced imaging.

“Areas where there is stress on the bone are not often available to us for observing with traditional forms of imaging like digital radiography,” Brown said. “PET scan technology can show us areas of active bone remodeling.”

Using statistics compiled through the EID, vets have learned that 85% of the musculoskeletal injuries that occur in racehorses involve the fetlock, the joint where the cannon bone, sesamoid bones, and long pastern bone meet above the hoof.

“Advanced imaging that gives us the capacity to have an impact on preventing fetlock failure in itself would be a monumental stride in moving the needle on preventing injury to the horse,” Brown stated.

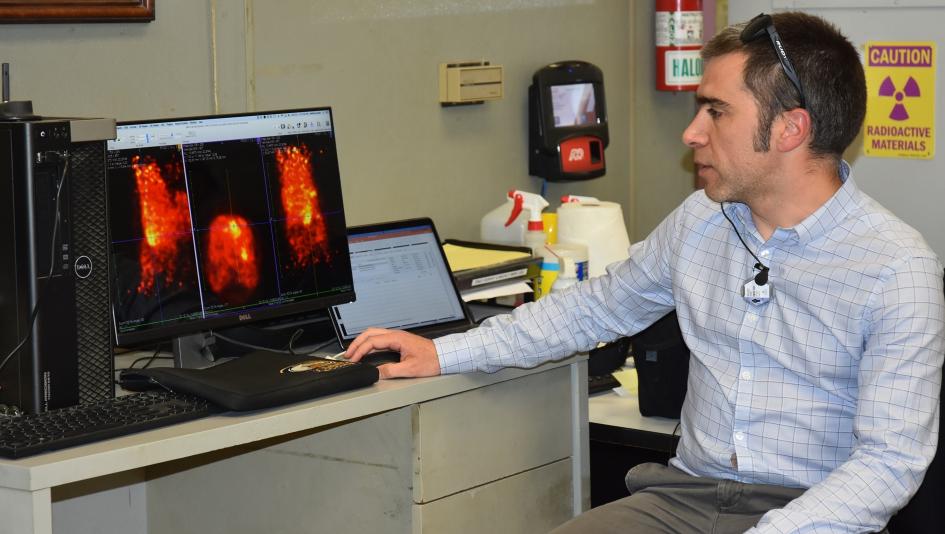

In PET scan technology, a sodium-based radium isotope is injected into the horse (just as is done when the technology is used to evaluate humans). The isotope acts as a highlighter. It seeks out metabolic activity in bone, with those areas appearing as bright, highlighted spots. The technology can identify changes and prevent potential fractures before they occur.

Santa Anita Park was the first racetrack in the world to install a PET scan on its grounds. In Kentucky, where clinics like Rood & Riddle Equine Hospital and Hagyard Equine Medical Institute are located close to major racetracks, horses are more likely to be referred to an off-track facility for advanced imaging. However, through an arrangement with Hagyard, Churchill Downs now operates a PET scan onsite.

A typical scenario would begin when a trainer, an attending vet, or a regulatory vet identifies a horse displaying an area of concern. Ultrasound and/or radiographs can be done at the track, but if they cannot determine the nature of the problem, advanced imaging comes into play. The horse will receive another lameness exam once at the clinic.

“We are looking at the activity of the turnover of the bone,” said Dr. Katie Garrett, director of diagnostic imaging at Rood & Riddle in Lexington. “As a horse trains, the load increases, and the bone gets stronger in response to the work you’re asking it to do. We worry when the bone is being asked to do too much, too soon. Once we’ve determined that we’re asking too much of them – each horse is an individual, so you can’t take a cookie-cutter approach – we can embark on a plan going forward.

“There are two types of imaging. Radiographs and CT scans are both structural imaging modalities, which tell us the structure of the bone, like the scaffolding around a building. They tell us what the bone is made of. Then there are PET scans and bone scans, which are functional imaging modalities that tell us what the bone is doing. We can often get the best information by combining the structural and functional modalities.

“We’ve had bone scans for decades, but the PET scan is more sensitive and gives us a more precise anatomical location. It gives us quantitative information and a more specific idea of where precisely in the bone the problem is happening.”

PET and CT scans can combine to confirm cases such as fractures that might benefit from insertion of a screw. But the good news for the racing environment is that many of the injuries diagnosed through advanced imaging can be solved by removing the horse from training for a period to give the bone time to catch up with what is being asked of it. Turnout is often recommended to give the animal a degree of exercise, and is preferable to stall rest, which inhibits the development of bone.

In 2019, Southern California saw a rash of catastrophic breakdowns. Besides the loss of horses and putting riders at risk, the equine deaths also led to a public relations disaster and calls for the termination of racing. Dr. Dionne Benson was brought in by 1/ST Racing, which owns Santa Anita Park and Golden Gate Fields, as chief veterinary officer to oversee safety protocols. The PET scan has been an important tool in reducing injury rates.

“Our fatality rate has been greatly reduced since 2019, and the PET scan is part of that,” noted Benson. “It allows us to catch things that we wouldn’t have been able to see before. We can now see the sesamoid bones at the back of the ankle and see metabolic change there. It picks up active bone remodeling, so it’s almost pre-fracture.

“We’re doing more than 100 PET scans a year now, as the attending vets and practitioners have embraced the technology. The biggest limitation we have is getting the radium isotope because it is human-grade medication, and people get first priority. The beauty of PET scans is that horses can walk from their stall to the imaging area, and they’re usually back in their stall within four hours. We also have a standing MRI and nuclear scintigraphy, allowing practitioners to use what they think is best.

“We’ve been able to diagnose soon and diagnose better, which translates to less downtime and fewer catastrophic injuries.”

The equipment required to perform advanced imaging is costly, running into seven figures because it has to be made specifically to accommodate the size of horses. However, the price of treatment is far from prohibitive. At Santa Anita, the imaging is conducted by the non-profit Southern California Equine Foundation, which keeps costs lower than outside clinics. Benson said that a PET scan costs less than $1,000 there.

“We’re working hard to keep costs down because we believe these modalities are so important,” she said. “We started a program up north where we help pay for advanced imaging in certain situations.”

Garrett noted that a PET scan in Kentucky runs about $1,500. Brown added that a number of avenues – including private funding, or the involvement of horseman’s groups or racing associations – are being explored as ways to make these treatments readily available to support the horses in the jurisdiction.

Brown believes that as the technology is used more frequently, it will result in even more positive outcomes for horses.

“I think this technology is huge for equine safety,” Brown stated. “The more we apply the results of this imaging to our knowledge base, the better we position ourselves to develop AI around the individual horse. It’s very exciting what these opportunities hold for us.”

Added Garrett, “I think this is a really important piece of how we continue to improve safety in racehorses. It’s not something that can be used alone, and it’s not best to use PET scans on a widescale screening basis. But it has the potential to help us identify a group of horses that could potentially sustain more severe injuries if we don’t intervene and take them out of training. And we want to make this sport as safe as we possibly can.”

Said Benson, “There is no doubt in my mind that advanced imaging is increasing equine safety. It would be great if there was one single bullet you could put over a horse and cover everything, but that doesn’t exist for horses, or humans. You need a full complement in addition to ultrasound and radiographs, and advanced imaging allows us to diagnose problems so much earlier.”